Catalog

This catalog highlights projects, people, groups, research, discussions, and other initiatives in the malleable software community. It is our hope that bringing more awareness to these efforts will lead to greater collaboration and better systems for us all that support the essential principles of malleability.

If you know of people, projects, threads, or anything else that should be added, please edit the wiki or send us a note. Similarly, please let us know about anything that should be removed or corrected.

Order in the catalog is randomised on each page load.

Projects, papers, and discussions

-

A Future of Programming.

2019.

Enable everyone, especially people from other domains outside programming, to take advantage of computation. Empower people to build their own systems and tools, giving them more of the powers that have only been available to programmers through writing code, so they can augment their own workflows in their own areas of expertise.

Blur the line between developers and users. Enable people to modify the systems and tools they use and adapt them to their needs.

-

A World Without Apps.

2019.

…with apps today, you are given full, complex software where you don’t have a choice. You have to have all of it or none of it, and you have to learn it, and you have relearn it at each update, and you have learn a different version when you shift from one vendor to another. (7:35)

…the key idea here is to make tools more generic, general, and independent of the environment in which they are going to be used. (12:50)

I often think about this [Samuel Johnson] quote from my late stepfather’s desk: ‘Nothing will ever be attempted if all possible objections must first be overcome.’ (20:51)

I also strongly believe that users should have a bit more control over security and the risks they are willing to take. We learn by doing, we learn by failing, we learn by doing mistakes, we learn by breaking things. And sometimes I want a secure environment and sometimes I want to see what happens if I put my fingers in the plug. (21:17)

I don’t think it is incompatible to have more flexible environments and security. What I’m advocating for is the ability for people to make choices. (23:24)

I do not believe that this type of change will come from the companies that dominate computing at the moment, in the same way that GUIs didn’t come out of IBM at the time. (30:43)

My take is not to try to directly address the wider audience, but to try with niche markets. (31:20)

-

An app can be a home-cooked meal.

2020.

Additional Resources

I made a messaging app for, and with, my family. It is ruthlessly simple; we love it; no one else will ever use it.

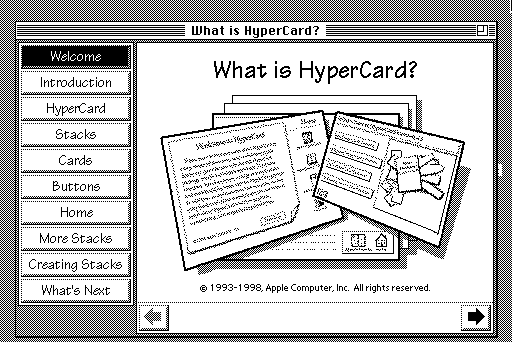

In a better world, I would have built this in a day using some kind of modern, flexible HyperCard for iOS, exporting a sturdy, standalone app that did exactly what I wanted and nothing else.

People don’t only learn to cook so they can become chefs. Some do! But far more people learn to cook so they can eat better, or more affordably, or in a specific way. Or because they want to carry on a tradition. Sometimes they learn just because they’re bored! Or even because — get this — they love spending time with the person who’s teaching them… I will gently suggest that perhaps coding might be entangled the same way… with our domesticity and comfort, nerdiness and curiosity, health and love.

-

Armories for tool-maker/tool-user collaborations.

2021.

Describes a deeper, more intense 2-person alternative to ecologies for tailorable software (summarized in Philip Tchernavskij’s Designing and Programming Malleable Software.

Great tools for thought rarely come from contexts focused on creating tools. They’re usually created in the course of deep creative work in some domain, almost as a byproduct. And they’re usually made by people with significant expertise and investment in those creative problems.

In most domains, great tool-makers are rarely great tool-users, and vice-versa. There might be advantages to separating the work: the tool-maker could constantly consider abstraction and generalization, and the tool-user could focus on meaningful problems at hand without being distracted by issues of systematization.

There’s a tricky chicken-and-egg problem here. If great creative work should drive the invention of new mediums, how can the initial idea driving the creative work get started in the first place?

The pair must proactively develop an armory of tool ideas to equip the tool-user’s explorations. Tool ideas in the armory don’t have to be working software. They just have to be understood well enough that the tool-user can tinker with them in emerging creative projects.

This conception is mostly useful in the context of repeated collaborations, particularly across distinct projects.

-

BETA (programming language).

1993.

Kristen Nygaard, the author of the first object-oriented language (SIMULA), went on to develop an interesting early OOP language called BETA.Additional Resources

This paper tells the story of the development of BETA: a programming language with just one abstraction mechanism, instead of one abstraction mechanism for each kind of program element (classes, types, procedures, functions, etc.). The paper explains how this single abstraction mechanism, the pattern, came about and how it was designed to be so powerful that it covered the other mechanisms.

The BETA project was started in 1976 and was originally supposed to be completed in a year or two. For many reasons, it evolved into an almost lifelong activity involving Nygaard, the authors of this paper and many others. The BETA project became an endeavor for discussing issues related to programming languages, programming and informatics in general.

-

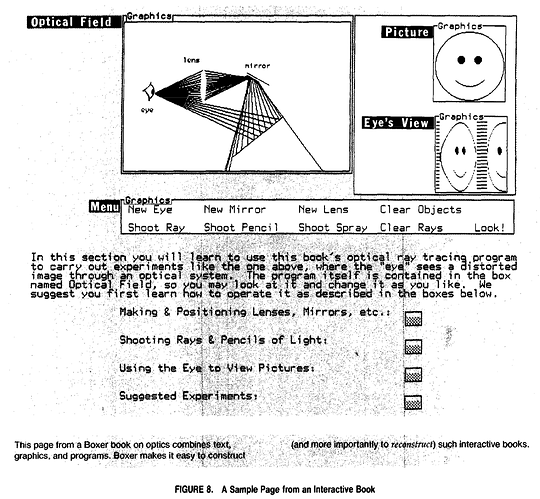

Boxer: a reconstructible computational medium.

1986.

One major benefit of programmability is that even professionally produced items become changeable, adaptable, fragmentable, and quotable in ways that present software is not.

… a reconstructible medium should allow people to build personalized computational tools and easily modify tools they have gotten from others. This concept is in strong contrast to the current situation in applications software — professionals are designing tools only for large populations with a common need.

Boxer challenges, in a small way, the current view of programming languages. More significantly, it challenges the current view of what programming might be like, and for whom and for what purposes programming languages should be created. We have argued that some computer languages should be designed for laypeople, and have presented an image of how computation could be used as the basis for a popular, expressive, and reconstructible medium. Computers will become substantially more powerful instruments of educational and social change to the extent that such an image can be realized.

-

Bring Your Own Client.

2021.

Today we generally think about BYOC at the “app” level. But can we go finer-grained than that, picking individual interface elements? Instead of needing to pick a single email client, can I compose my favorite email client out of an inbox, a compose window, and a spam filter?

-

Browser extensions are underrated: the promise of hackable software.

2019.

Among major software platforms today, browser extensions are the rare exception that allow and encourage users to modify the apps that we use, in creative ways not intended by their original developers. On smartphone and desktop platforms, this sort of behavior ranges from unusual to impossible, but in the browser it’s an everyday activity.

Since the beginning of personal computing, there’s been a philosophical tradition that encourages using computers as an interactive medium where people contribute their own ideas and build their own tools—authorship over consumption.

-

Brutalist HTML quine.

2019.

This technique uses CSS magic to expose the full tag structure underlying the page.

<p>A different but somehow related topic I like is<a href="https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brutalist_architecture">brutalism</a>, in particular, this often overlooked aspect:</p><blockquote>Another common theme in Brutalist designs is the exposure of the building’s functions.</blockquote><p>…the tendency to<strong>make the internal external</strong>, and reveal the secrets of the building, in a somehow….<em>brutaful</em>way. ;-).</p> -

Convivial Design Heuristics for Software Systems.

2020.

Consider how many web applications contain their own embedded ‘rich text’ editing widget. If linking were truly at the heart of the web’s design, a user (not just a developer) could supply their own preferred editor easily, but such a feat is almost always impossible. A convivial system should not contain multitudes; it should permit linking to them.

The battle for convivial software in this sense appears similar to other modern struggles, such as the battle to avert climate disaster. Relying on local, individual rationality alone is a losing game: humans lack the collective consciousness that collective rationality would imply, and much human activity happens as the default result of ‘normal behaviour’. To shift this means to shift what is normal. Local incentives will play their part, but social doctrines, whether relatively transactional notions such as intergenerational contract, or quasi-spiritual notions of our evolved bond with the planet, also seem essential if there is to be hope of steering humans away from collective destruction.

-

Crochet.

2021 – present.

Crochet is a tool for creating and remixing interactive stories, safely.Additional Resources

- What's Crochet: A general description of the Crochet programming system

- Design Philosophy: Principles that guide Crochet

Crochet goes to great lengths to make creating, running and remixing content as safe and privacy respecting as possible. Content built with Crochet can only use your computer and your data in ways you explicitly consent to—it can’t change your files or send your information over the internet without your knowledge and consent.

One of the core principles of Crochet is that you should feel safe to experiment with your computer as much as you want, without having to worry about questions like: “If I install this application, will it try to steal my files?” or “What if I try this and it breaks my computer?”

Crochet is a “language-driven” system, through the lenses that we interact with computational concepts through languages; Even “direct manipulation” forms a language, where the ways in which we can manipulate things is dictated by a set of composable rules. A system like this, heavily dependent on tooling, needs ways in which users can extend the system to fit their own context. This means that Crochet has to support user-extensible IDEs, user-extensible Debuggers, user-extensible REPLs, etc. And these users should be able to modify any aspect of these tools to fit new languages (interactions, manipulations, rules, etc).

-

Decker.

2022 – present.

A multimedia platform for creating and sharing interactive documents, with sound, images, hypertext, and scripted behavior.

Additional Resources

Additional ResourcesDecker builds on the legacy of HyperCard and the visual aesthetic of classic macOS. It retains the simplicity and ease of learning that HyperCard provided, while adding many subtle and overt quality-of-life improvements, like deep undo history, support for scroll wheels and touchscreens, more modern keyboard navigation, and bulk editing operations.

Anyone can use Decker to create E-Zines, organize their notes, give presentations, build adventure games, or even just doodle some 1-bit pixel art. The holistic “ditherpunk” aesthetic is cozy, a bit nostalgic, and provides fun and distinctive creative constraints. As a prototyping tool, Decker encourages embracing a sketchy, imperfect approach. Finished decks can be saved as standalone .html documents which self-execute in a web browser and can be shared anywhere you can host or embed a web page. Decker also runs natively on macOS, Windows, and Linux.

-

Designing and Programming Malleable Software.

2019.

The contemporary landscape of interactive software operates as a “designer-knows-best” model that gives users very few opportunities to change their software or to make different pieces of software work together as they see fit.

I introduce malleable software as a design vision that reconstructs the goals of tailorable systems with pluralism as a guiding value. Malleable software is made up of interface elements untangled from the closed worlds of apps, which can be developed by different authors and (re-)combined by end users.

-

Dynamicland.

2017 – present.

Dynamicland is a communal computer, designed for agency, not apps, where people can think like whole humans.

No normal person sees an app and thinks ‘I can make that myself.’ Or even ‘I can modify that to do what I actually need.’ Computational media in Dynamicland feels like stuff anyone can make. … A humane dynamic medium gently leads people down a path from playing, to crafting, to remixing, to programming.

Dynamicland is an authoring environment, and everyone is an author. People make what they need for themselves. They learn through immersion. The true power of the dynamic medium — programmability — is for everyone.

-

Encoding for Robust Immutable Storage (ERIS).

2022.

ERIS is an encoding of arbitrary content into a set of uniformly sized, encrypted and content-addressed blocks as well as a short identifier that can be encoded as an URN. The content can be reassembled from the blocks only with this identifier. The encoding is defined independent of any storage and transport layer or any specific application.

-

End-user programming.

2019.

Desktop programs, web apps, and smartphone apps are to various degrees like appliances with a hermetic seal to keep users out of their interior. If there is not already a button for a given function, the only option for users is to petition the developer.

There shouldn’t be a chasm that the user has to cross in order to customize the behavior of their software. Going from using to inspecting to modifying the system should be a gradual process where each of the steps is small enough to be easily discoverable. The user should not need to switch to “programmer mindset” but instead stay within the context of the application. They can stay close to their work and their ideas.

-

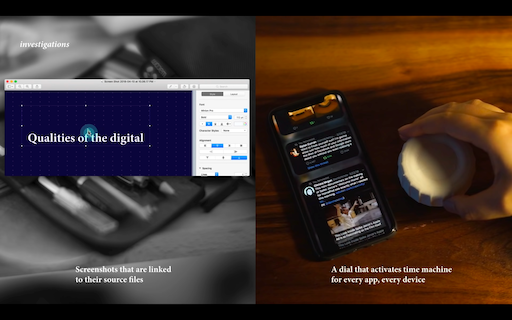

folk.computer.

2023 – present.

Folk is a physical computing system: reactive database, programming environment, projection mapping. Instead of a phone/laptop/touchscreen/mouse/keyboard, your computational objects are physical objects in the real world, and you can program them inside the system itself. Folk is written in a mix of C and Tcl.Additional Resources

-

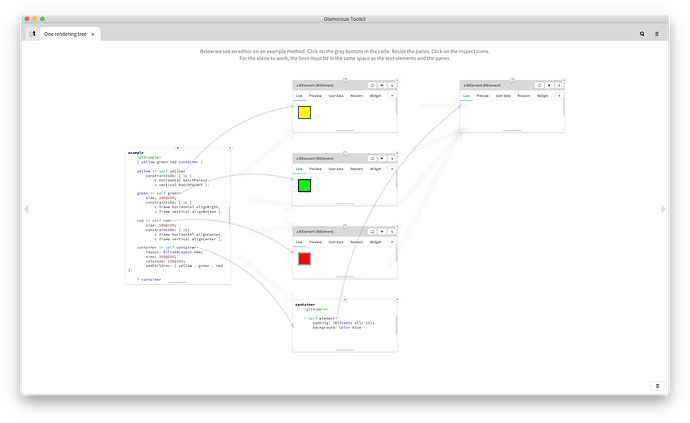

Glamorous Toolkit.

2017 – present.

Glamorous Toolkit is the moldable development environment. It is a live notebook. It is a flexible search interface. It is a fancy code editor. It is a software analysis platform. It is a data visualization engine. All in one. And it is free and open-source under an MIT license.

We want the environment to fit the context of the current system and when it does not, we want to be able to mold it live. This seemingly small change is transformational and can be utilized in many ways.

Whatever is shown on the screen is rendered in one single rendering tree. No canvas in between. That means that all layouts are regular layouts, including the graph layouts and text-editor layouts. That means that text is made of regular elements. And that means that all elements can be combinable without imposing a technical limit.

-

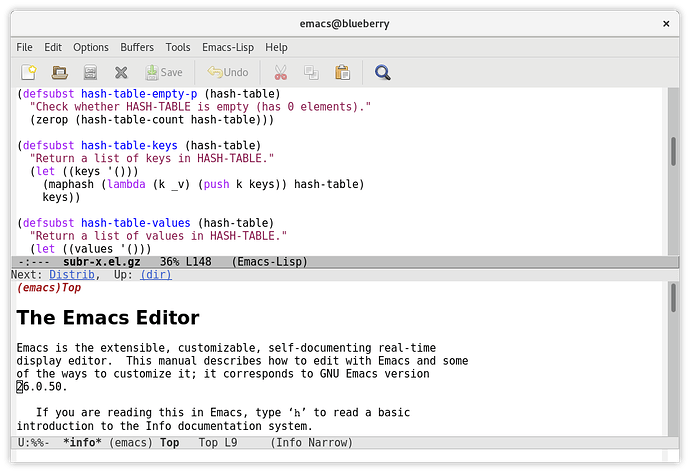

GNU Emacs.

1976 – present.

Extensible means that you can go beyond simple customization and create entirely new commands. New commands are simply programs written in the Lisp language, which are run by Emacs’s own Lisp interpreter. Existing commands can even be redefined in the middle of an editing session, without having to restart Emacs. Most of the editing commands in Emacs are written in Lisp; the few exceptions could have been written in Lisp but use C instead for efficiency. — GNU Emacs manual, Introduction

Org can be used as a TODO lists manager and as a planner. Org is a great plain-text table editor. Org is an authoring and publication tool. Org makes literate programming a handy and natural way to deal with code. — Org mode feature list

This appendix covers some areas where users can extend the functionality of Org. — Org mode manual, Appendix A Hacking

-

HyperCard.

1987 – 2004.

HyperCard is a software erector set that lets non-programmers put together interactive information — Bill Atkinson, Computer Chronicles (1987)

HyperCard’s biggest win was a very low entry threshold for those who wanted to build their own ‘stacks’ - combinations of user interface, code, and persistent data. There were plenty of examples to suggest ideas, and all the code was open for tweaking. — Tim Oren, A Eulogy for HyperCard (2004)

-

liballocs.

2011 – present.

Meta-level run-time services for Unix processes… a.k.a. dragging Unix into the 1980s

Unix abstractions are fairly simple and fairly general, but they are not humane, and they invite fragmentation. By ‘not humane’, I mean that they are error-prone and difficult to experiment with interactively. By ‘fragmentation’, I mean they invite building higher-level abstractions in mutually opaque and incompatible ways (think language VMs, file formats, middlewares…). To avoid these, liballocs is a minimal extension of Unix-like abstractions broadly in the spirit of Smalltalk-style dynamism, designed to counter both of these problems.

-

Lopecode: Self-editing, humanely embeddable Observable notebooks.

2025.

Announced by Chris Shank in this Bluesky postingAdditional Resources

The hermetic, self-hosted, self-sustainable, recursively exportable, offline-first, file-first, web-based reactive open-source programming substrate built on observable runtime is online finally!

The editing experience is not there yet. Probably wiser to fork the original Observable notebook if you seriously want to create a webpage.

-

McCulloch-Pitts Neural Nets.

2025.

In exploring parallel rewriting systems, I stumbled onto something like neural networks and it pushed me to dive deeper into the topic and learning how they worked. I was surprised how capable this nice little OISC was. I implemented a textual graph representation language and runtime in about 150 lines of C89, or about 300 lines of Uxn. I think this is relevant to the Malleable community due to it being a symbolic system which is popular with malleable systems, as well as people exploring portable and parallel computation models.

- Micro-PROLOG. 1983.

-

milliForth: Forth in 380 bytes (on x86).

2023.

Additional Resources

A FORTH in 336 bytes — the smallest real programming language ever, as of yet.

-

Myths and mythconceptions: What does it mean to be a programming language, anyhow?.

2022.

The steep learning curve for these languages is a barrier to entry for many people. Part of the reward for this effort is an associated mystique about having mastered the special knowledge.

As computation has become pervasive, more and more people who are not professionally trained as programmers are creating and tailoring software as a means to achieve goals of their own. These vernacular software developers are principally interested in their own tasks, not in the software as a primary objective.

Many vernacular software developers are highly trained in their own domains and only lightly trained in traditional programming. They use a variety of tools and notations including spreadsheets, scripting, data schemas, markups, domain-specific languages, visual web development tools, and scientific libraries.

Without adequate specifications for the components, there’s no way to reason formally about the result. When owners of components can change them without notice, users have no assurances. As a result, formal verification is, on the whole, a minor player for real software.

-

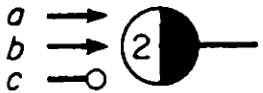

Nova: Multiset Rewriting Language.

2024.

Nova is a rewriting language with a very simple core that holds a fantastically comfy UX to program in, to extend, to communicate with over a wire, take dynamic notes in, etc.Additional Resources

-

Pad++: a zooming graphical interface for exploring alternate interface physics.

1994.

A zoomable graphical sketchpad. Documentation and more information can be found here.

… Pad++, an infinite resolution sketchpad that we are exploring as an alternative to traditional window and icon-based approaches to interface design.

There are numerous benefits to metaphor-based approaches, but they also lead designers to employ computation primarily to mimic mechanisms of older media. While there are important cognitive, cultural, and engineering reasons to exploit earlier successful representations, this approach has the potential of underutilizing the mechanisms of new media.

We envision a much richer world of dynamic persistent informational entities that operate according to multiple physics specifically designed to provide cognitively facile access. The physics need to be designed to exploit semantic relationships explicit and implicit in information-intensive tasks and in our interaction with these new kinds of computationally-based work materials.

-

Pinocchioverse.

2023.

Pinocchioverse is a fictional, educational programming language based on the idea of coding with marbles. It is defined by a fictional universe, in which, due to the natural laws of the universe, programs can be “built” with marble runs.

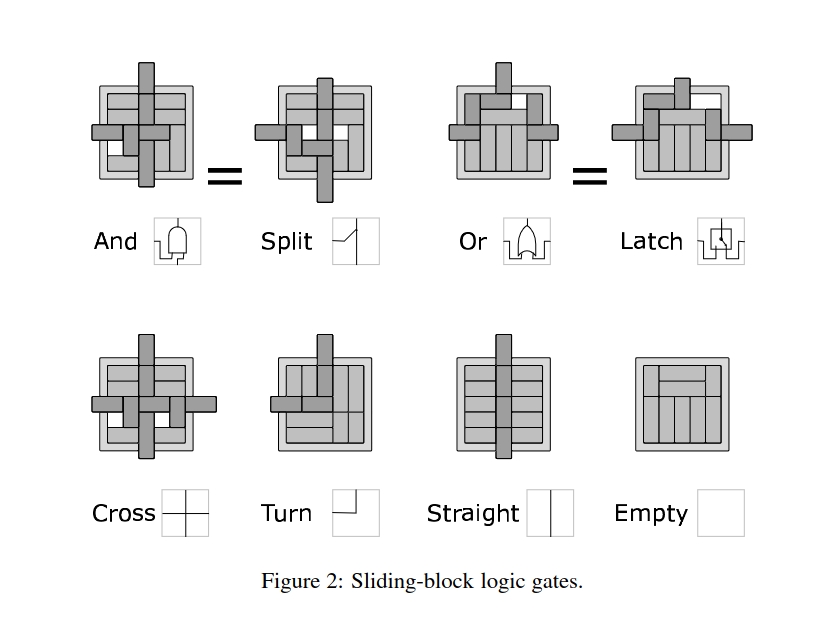

- Sliding Blocks Computing. 2003.

-

Smallscript: A Smalltalk-inspired Scripting Language.

2024.

The interesting feature of Smallscript is the set of slight changes and modernizations it makes to classic Smalltalk syntax.

-

Smalltalk.

1972 – present.

A programming language and in-context development environment with powerful built-in tools like a class browser, object inspector, and debugger.

The message is the most fundamental language construct in Smalltalk. Even control structures are implemented as message sends. — Wikipedia

The late-bound, message-based interfaces of objects provide strong interposability properties: clients remain oblivious of the specific implementation they are talking to. In turn, this simplifies the customisation, extension or replacement of parts of a system, all of which can be rendered as interposition of a different object on the same client. — Stephen Kell, The operating system: should there be one? (2013)

-

Software as a “place”.

2019.

What makes a piece of software a “place” vs a “tool” or an “appliance”? … I think some notion of limitlessness and nesting are necessary. [The feeling of a “place”] seems to come from some kind of limitlessness: Notion has infinite hierarchies, Figma has an infinite canvas. … This definition matters to me because appliances are static, but places can be occupied and changed. You can have memories and experiences in them. Things can grow in them. New stuff can emerge. Communities can form. I want more software to be like that.

-

Syntropize: An Operating Environment for Malleable Software.

2022 – present.

Syntropize is a proposal for a malleable software operating environment, an attempt to reclaim the original vision of personal computing as the means to augment human intellect.Additional Resources

-

Tangible Functional Programming.

2007.

Additional Resources

We present a user-friendly approach to unifying program creation and execution, based on a notion of “tangible values” (TVs), which are visual and interactive manifestations of pure values, including functions. Programming happens by gestural composition of TVs. Our goal is to give end-users the ability to create parameterized, composable content without imposing the usual abstract and linguistic working style of programmers. We hope that such a system will put the essence of programming into the hands of many more people, and in particular people with artistic/visual creative style.

-

The future of software, the end of apps, and why UX designers should care about type theory.

2013.

Software is now organized into static machines called applications. These applications (“appliances” is a better word) come equipped with a fixed vocabulary of actions, speak no common language, and cannot be extended, composed, or combined with other applications except with enormous friction.

Applications can and ultimately should be replaced by programming environments, explicitly recognized as such, in which the user interactively creates, executes, inspects and composes programs.

Applications are failing at even their stated goal, but they do worse than that. Yes, an application is an (often terrible) interface to some library of functions, but it also traps this wonderful collection of potential building blocks in a mess of bureaucratic red tape.

No one piece of software ‘does it all’, and so individuals and businesses looking to automate or partially automate various tasks are often put in the position of having to integrate functionality across multiple applications, which is often painful or flat out impossible. The amount of lost productivity (or lost leisure time) on a global scale, both for individuals and business, is absolutely staggering.

As a civilization, we would be better off if software could be developed by small, unrelated groups, with an open standard that allowed for these groups to trivially combine functionality produced anywhere on the network.

The problem is, I don’t want a machine, I want a toolkit, and Google keeps trying to sell me machines. Perhaps these machines are exquisitely crafted, with extensive tuning and so forth, but a machine with a fixed set of actions can never do all the things that I can imagine might be useful, and I don’t want to wait around for Google to implement the functionality I desire as another awkward one-off ‘feature’ that’s poorly integrated and just adds more complexity to an already bloated application.

-

The mythical matched modules: overcoming the tyranny of inflexible software construction.

2009.

Conventional tools yield expensive and inflexible software. … I propose that a solution must radically separate the concern of integration in software: firstly by using novel tools specialised towards integration (the “integration domain"), and secondly by prohibiting use of preexisting interfaces (“interface hiding”) outside that domain.

Placing high-level tool support for integration and adaptation close to the user, for example within web application mashup platforms and browser extensions has already led to added-value innovations which could not have been anticipated by the creators of the underlying software.

-

The “Space” of Computing.

2018.

Our conception of “computing” has changed and continues to change. This work identifies dimensions that constitute the “space of computing”.

Currently, only those who have a programming background or resources have the ability to create digital artifacts. This forces the rest of the world to be consumers, rather than creators or authors. When creating digital products, our conception of target audience is “users”. The notion of “users” sometimes assumes that their main goal is consuming instead of playing, creating, or conversing. What if the digital environment was inclusive enough for anyone to create? How can we provide the tools that will enable everyone to become authors?

-

The Syndicated Actor Model.

2012 – present.

Functional programs are easy to write, but programs that interact with each other and the outside world are much harder. Programming models like the Actor model and the Tuplespace model make great strides toward simplifying programs that communicate. However, a few key difficulties remain. The Syndicated Actor model addresses these difficulties. It is closely related to both Actors and Tuplespaces, but builds on a different underlying primitive: eventually-consistent replication of state among actors. Its design also draws on widely deployed but informal ideas like publish/subscribe messaging.

-

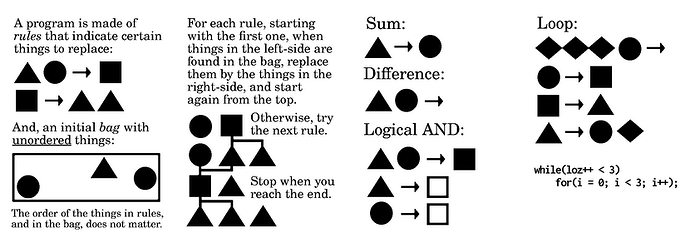

Tote: Multiset Rewriting Language.

2025.

I’ve been interested for a while in symbolic visual programming, and I made a IDE to test some ideas around writing GUIs entirely in multiset rewrite rules. Tote is a playground that lets me play with some of these ideas. I think it’s relevant to malleable systems because it presents programming in its most elementary form (a single while loop), and can be implemented easily on near anything at all, in fact, all you need for this is a bag with marbles of different shapes or color.

-

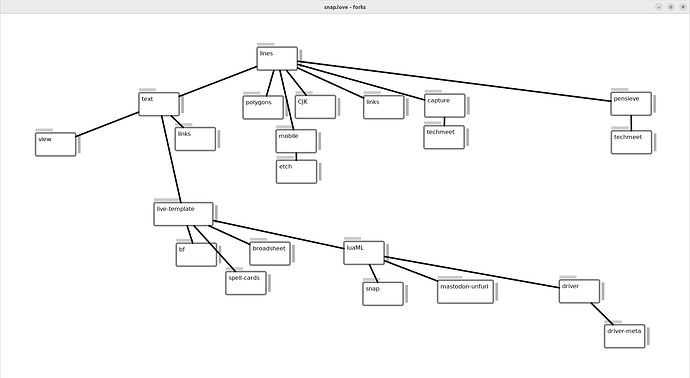

Using computers more freely and safely.

2023.

Manifesto for Freewheeling Apps and experience report in trying to create situated software. Argues for building situated software out of situated tools that are parsimonious in dependencies and infrequently updated.

- with thousands rather than millions of users

- that seldom requires updates

- that spawns lots of forks

- that is easy to modify

- that you can modify

Prefer software:

-

Wang Tiles Computing.

2012.

Wang pointed out that it is possible to find sets of Wang tiles that mimic the behaviour of any Turing Machine (Wang 1975). A Turing machine can compute all recursive functions, that is functions whose values can be calculated in a finite number of steps. That is to do, however inefficiently, what any conceivable computer can do. The basic idea is to use rows of tiles to simulate the tape in the machine, with successive rows corresponding to consecutive states of the machine.

-

What Lies in the Path of the Revolution.

2018.

We argue that a form of “digital serfdom” has rapidly grown up around us, where various important classes of artefacts, increasingly essential for everyday life, including participation in political and economic life, cannot be effectively owned by ordinary individuals.

Many of the technological barriers to ownership, especially as regards software, can be seen as embedded in certain questions of “reuse” — one of the central affordances of ownership is the ability to transplant a thing from its original location to a different one, following the desires or person of the owner. For most kinds of software this is possible in only a crude way — an “application” can be installed on one machine rather than another — and with the rising prevalence of rental or cloud-based models for the deployment of software, it is decreasingly possible at all.

If you find a piece of software that does something of value to you, it should be possible to make it your own. This implies that you can keep using it as part of the collection of tools you carry with you, in familiar contexts, or experiment with using it in novel contexts.

-

Wildcard: Spreadsheet-Driven Customization of Web Applications.

2020.

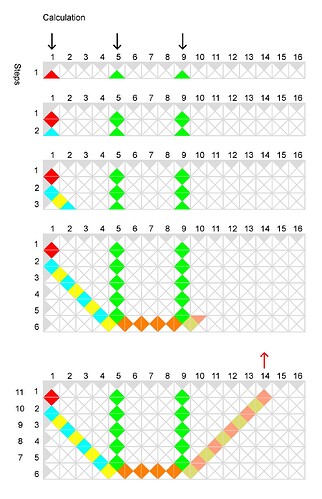

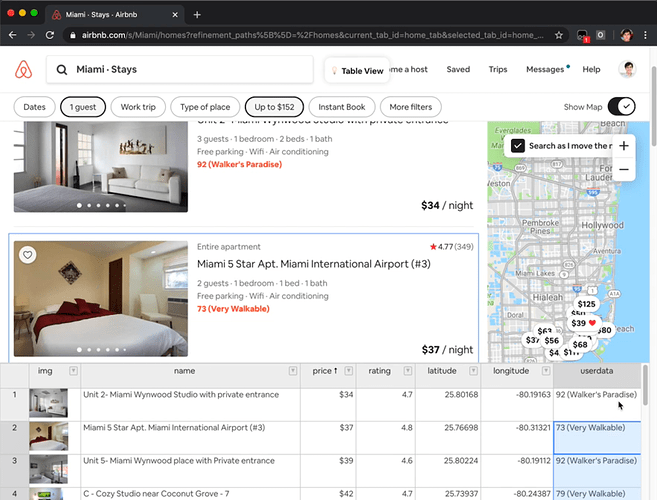

In this paper, we present spreadsheet-driven customization, a technique that enables end users to customize software without doing any traditional programming. The idea is to augment an application’s UI with a spreadsheet that is synchronized with the application’s data. When the user manipulates the spreadsheet, the underlying data is modified and the changes are propagated to the UI, and vice versa.

Generic tools are especially important for software customization, because a common barrier to customizing software is not having enough time [Mackay 1991]—it’s more likely that people will customize software frequently if they can reuse the same tools across many applications.

One of the most interesting properties of spreadsheets is that users familiar with only a tiny sliver of their functionality (e.g., storing tables of numbers and computing simple sums) can still use them in valuable ways. This supports the user’s natural motivation to continue using the tool, and to eventually learn its more powerful features if needed [Nardi and Miller 1991].

People and groups

The following people and groups are some of the key actors in this space due to their work highlighted above, which has been curated through contributions to the catalog from the community. Please note that you should not assume that they have endorsed the community's actions — we simply admire their work.

-

Antranig Basman

Raising the Floor - International -

Clemens N. Klokmose

Aarhus University -

James R. Eagan

Télécom Paris -

Geoffrey Litt

MIT -

Ink & Switch

-

J. Ryan Stinnett

King's College London -

Stephen Kell

King's College London -

Weiwei Xu

California College of the Arts -

Yoshiki Schmitz